Every time I take the exit for I-80 West, signaling the last stretch on my drive to Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, I feel an overwhelming sense of relief; not unlike the feeling of stepping through the front door of your house after a grueling week of work. It’s a loosening of the chest; an involuntary deep sighing of relief; a subtle lifting of the heart.

It’s the feeling of coming home.

This reaction is somewhat puzzling because my time as an undergraduate student at Bucknell University comprised some of the most challenging and stressful years of my life. However, those years also coincided with my discovery of cycling, and the true beginning of my love for the sport. It was in the countryside and hills of central Pennsylvania where I fell in love with two-wheeled adventures which, I suppose, makes all bike related trips to Lewisburg feel a bit like poetically closing some loop of fate.

On the last stretch of I-80, as we neared the exit for Lewisburg toward Bucknell University, I was reminded of how much I love the central Pennsylvania countryside: the golden fields of corn, the foliage-quilted ridges rippling along the interstate, and the cows grazing out in distant pastures while their owners navigate heavy tractors through dusty brown fields.

Our Airbnb was an old brick school house converted into a one bedroom cottage. It is nestled in the Lewisburg farm fields, adjacent to chicken and cow farms, with a gorgeous view of the surrounding area. This was the perfect backdrop to what I hoped would be the perfect ending of my race season in an otherwise very imperfect year.

Our own slice of solitude.

Cows! One of our friendly neighbors. (Photo credit: Joe)

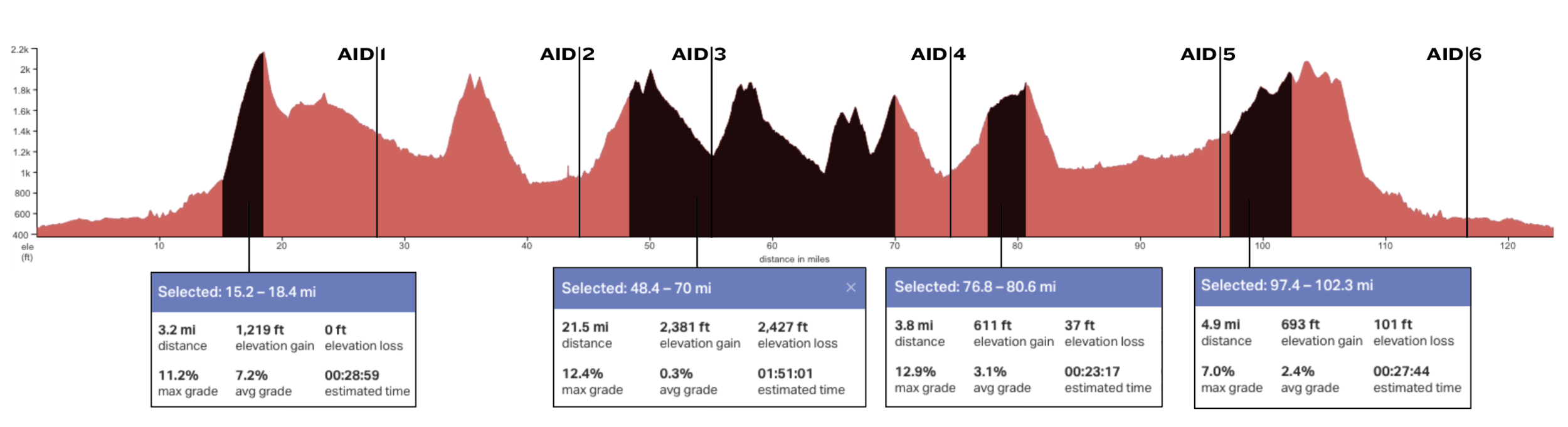

unPAved 2020 looked quite different compared to the 2019 version. As you might expect, this was largely due to the Covid-19 pandemic. For starters, all participants had to register for the 123-mile course and there was a maximum of 200 participants. Next, there would be no pre- or post-race gathering with the race participants, staff, and locals; the race day event was the singular opportunity to connect with the unPAved community this year. Finally, race timing would be different than previous years. While the course itself is similar to last year, racers would be timed only on 4 very specific segments of the course (somewhat like enduro racing, for you mountain bike fans). The rest of the course was considered neutral riding and racers were encouraged to take their time, enjoy the views, and respect the volunteers’ and fellow racers’ safety at the aid stations.

In total, there were about 33.5 miles (and 4,900 feet) of actual racing on course.

Black seems like an unusually cruel color to mark the four grueling segments of pain on the unPAved 2020 course.

The segment racing format freaked me out. How would I pace myself? Would I ever see anyone else on course? This was all new territory for me.

As the race date neared, the unPAved crew announced a Covid-safe plan for individual call-ups and race starts, with 30-seconds between each participant. Racers would be called up by an Amish auctioneer (how cool is that?) and sent off to navigate the course alone. Upon reviewing the start times, I noticed that the race organizers had arranged for me to start DEAD LAST of all racers for the day, just before 9am AND I was assigned race number 1. Last year’s runner up, Hayley, was number 2, and second place from the 2018 edition unPAved, Vicki, was number 3. The three of us were the last three racers assigned to leave for the day, which was a subtle way of showcasing the strong women cyclists at the event, even though the race organizers were very aware that some men would certainly be faster than us. (Let’s take a very long pause here to appreciate how absolutely rad this is. Thank you to the unPAved crew for this statement about the importance of showcasing women in cycling, in an industry that falls short with regard to gender equality in almost every way possible.)

Unfortunately, the individual call-up plans were foiled by an impending hurricane, so the organizers gave everyone the choice to start anytime they wanted, between 7:30 - 9am. When I read this news, I was somewhat relieved, because I knew the original plan would likely result in me grouping up with Hayley and Vicki, and then we’d have to ride together, which made me uncomfortable. What if we got sick of each other? What if someone didn’t want to ride with the group? What if I was feeling horrible and I got dropped on the race segments? Or worse, what if I was feeling phenomenal and I still got dropped on the race segments, watching my chances of winning disappear? Would we re-group? What if someone got a flat tire? All of these “what ifs” were uncertainties that could be easily mitigated if I raced on my own, away from everyone else, just like I always have in the past.

It’s important to note that with very few opportunities to race this year (i.e., unPAved was the second of only two races in 2020), I wanted to be intentional about my mindset and how I chose to show up for this race. In previous races, I have focused only on myself and tried to conjure some illusion that I have control over everything. Additionally, I have always focused on winning at any cost (within reason of course). This is the result of being incredibly competitive my whole life.

But 2020 has given me time to grow and reflect. This year, I knew Hayley was going to have a fire in her after what happened in the 2019 edition (read this blog post about 2019 unPAved if you’re unfamiliar). All I wanted was a real race, unencumbered by mechanicals or navigation issues, won by the strongest racer that day. Indeed I wanted to be the strongest racer on the day, but I also didn’t want to win at the cost of someone else’s misfortune. Last year’s win (Hayley took a wrong turn in the last ~10 miles) felt disingenuous and has been heavy on my mind for a year. This year, I told myself that if I’m going to win, I want to feel proud of myself; if I don’t win, I still want to end the day feeling proud. That was the goal: an honest performance that required me to dig deep and give my all—whatever that meant in a year when racing was almost non-existent.

My coach and I reflected on the unique opportunity this race situation provided. Indeed my mind was full of all the things that could go wrong. But perhaps I wasn’t focusing on an even more important question...What if everything went right? This was, I’ll admit, a potential outcome I hadn’t considered.

Ultimately, I reached out to both Hayley and Vicki and proposed the idea of riding together for the day. I suggested we ride the neutral portions together, race the segments at our own pace, and then re-group at the end of each segment. It was a plan that ensured the three of us would have company for the entire ride, and would give us the opportunity to push each other in the segments by starting together.

Never in my racing career have I invited this kind of vulnerability into my race day. I felt completely exposed by this plan. The moment I sent the message to both of them, I immediately dreaded what would happen next. This would be the ultimate test of whether I could stack up against Hayley’s fire and Vicki’s experience. It felt like I was relinquishing some piece of control that was vital to maintaining the illusion that I was worthy of being labelled as a “Pro”. But, it was also a feeling of freedom and growth. I was shedding the old toxic competitiveness and inviting discomfort. I was showing up in 2020 in a way I never expected. This year, I chose to be truly present and enjoy the company of other female racers in a situation that made me feel incredibly vulnerable.

To my surprise, both Hayley and Vicki accepted the invitation. For better or worse, the plan was set.

On race day, the weather was almost perfect. It was a bit chilly to start but was supposed to warm up to high 60’s or even 70 degrees. The three of us met in the parking lot and I introduced Hayley and Vicki to each other. I was especially quiet that morning, recognizing that I was completely unsure how the day would unfold, and the lack of control made me anxious.

Making small talk before rolling out for the day. (Photo credit: Joe)

We rolled out on the exceptionally maintained Buffalo Valley Rail Trail, headed toward Jones Mountain. Immediately, I felt at ease. The three of us were talking about riding, work and the impact that the pandemic has had on our lives. For some portions, we rode in silence. It wasn’t awkward or uncomfortable but rather, it felt natural and almost as though we had been riding buddies for much longer than the single hour we had been riding together. In all honesty, the only awkward part of the entire ride is probably how many times I made them stop because I had to pee. Maybe you thought I would have this dialed in by now. Nope, I still haven’t perfected the art of hydration.

Segment 1 began at the base of a 3.5 mile climb up Jones Mountain. When the segment started, I was feeling quite strong, but it was obvious Hayley was too. The climb is quite steep and is mostly rough gravel, which makes finding a smooth rhythm difficult. Clearly, Hayley was stronger at that point in the race, and she pulled away relatively quickly, just as she had in almost the exact same spot in the 2019 edition of unPAved. I kept her in sight for a while, but also knew that if I dug too deep, I’d have nothing left for the next three segments of racing. Importantly, The Difference (Segment 2) was still many miles away and was going to require some serious grit and strength. I tried my best to keep in contact with her but eventually she was out of sight and I had estimated she was waiting at least two minutes at the top of the climb. All I could think at the end was “Damn, Hayley is a strong climber”. As I passed the “Segment Finish” sign, I realized I would need to tap deep into the unused race reserves of 2020 if I wanted any chance of winning the day.

The three of us re-grouped and rolled our way down the mountain past a phenomenal vista filled with foliage-lined mountains.

One of the many beautiful vistas of the Susquehanna River Valley.

The Difference segment (Segment 2) was on my mind from the moment we finished Segment 1. I remembered from last year that it was incredibly rocky and technical, with no relief from the jagged terrain for nearly 5 miles, the last 4 of which are downhill. That said, while Hayley is an expert climber on the bike, I’d like to think my mountain bike racing experience makes me equally as strong at technical riding, even on a gravel bike. Moreover, I was very confident that my bike was one of the (if not, the) most capable bikes on course that day.

The race day steed: Seven Cycles KellCross SL (a race optimized Evergreen SL) with SRAM Force shifters and brakes. Industry Nine i9.35 wheelset with Torch hubs. Vittoria Terreno Dry tires (700x38c). Ergon SR Pro Women’s Saddle. Nittany Mountain Works tool roll and stem bag, for supplies and backup snacks. (Photo credit: Joe)

Segment 2 started at the beginning of the technical portion of The Difference. I began the segment slightly behind Hayley and Vicki because I had to stop to pee (again…) and I told them they didn’t need to wait for me. Crossing the start line felt like a light switch turned on inside me. I was in my element—technical riding on a super fun bike felt akin to a mountain bike race. I caught and then passed both Hayley and Vicki and then continued to push through at a blazing pace. With each new line I picked, dodging the loose small boulders, my energy increased. In my head, I was singing a song that my dad and I used to listen to before my high school cross country races: “Dreams” by Van Halen (RIP Eddie Van Halen). The music ignited an energy that propelled me forward.

The one thing I tried not to do for the duration of this segment was look behind me. I didn’t want to know if Hayley or Vicki were close to me. I didn’t want to get comfortable and feel like I could hold back or conserve my energy. The Difference was my opportunity to leverage a potential lead with the first technical 5 miles, and then turn myself inside out for the next 16 miles. And that’s exactly what happened. I put my head down, rocked out to my song over and over, and smiled my way through pain, past fellow racers, and up some soul-crushing climbs all the way to the finish of Segment 2. As I caught my breath, I waited for Hayley before heading down to the next aid station.

We re-grouped at the next aid station in Poe Paddy State Park. There have been some rumors floating around that the “Roving Girl Gang” (as we were called some days after the race) had a mid-race picnic. I might have blacked out if we had anything resembling a peaceful, bountiful picnic, but if any of our aid station stops were going to be deemed picnic-worthy, I’d say this was the one. While we did stop at every aid station for water refills, it was during this stop after Segment 2 when we took our longest break. I even ate half of an almond butter and banana sandwich! The three of us were quite exhausted after crushing The Difference, and we knew Segment 3 was going to start only a few miles after rolling out of this aid station. So, we soaked in the reprieve, ate some snacks, took a moment to pee again (of course!), and chatted for a few minutes. I suppose that counts as a picnic?

Here you can see the fierce 1, 2, and 3 plated riders, in their element. (Photo credit: Abe Landes/Firespire Photography)

I know many of my followers were hoping to read about some harrowing food-related journey I experienced on race day. I’m shocked and also proud to say there’s no such tale to tell. Unlike the Dry Pretzel Fiasco of 2019, I was much more prepared for fueling the 2020 edition after months of experimenting during the pandemic. My bottles were filled with Flow Formulas drink mix, a high-carb fuel source, which was my primary energy for the day. That said, while fueling wasn’t an issue this year, I still had trouble balancing my hydration as I mentioned before. When all was said and done, the day consisted of at least 6 (honestly, I lost count) pee breaks. Joe regularly reminds me that I pee more than physiologically possible. He’s not a doctor, but he might be onto something.

Only a few short miles after rolling out of the Poe Paddy aid station, we took a sharp turn onto a steep gravel climb. As if on cue, the three Roving Girl Gang members noticed the “Segment Start” sign at the roadside. This steep pitch was the start of Segment 3, and none of us felt ready -- both mental and physically. With heavy legs and sunken hearts, we started the racing grind. If I recall through the haze of exhaustion, I think I muttered something like “I might actually cry right now”. Yet, after a couple minutes, Hayley and I had settled into our race pace, each choosing our own tire rut on either side of the road. Like some unspoken rule, she and I decided to ride side-by-side “drag racing” style, rather than draft each other. Perhaps, like me, she had a stubborn, competitive side that wanted this race to come down to personal strength and power, rather than drafting technique. In turn, we would each throw in a surge to pick up the pace as the climb continued. Ultimately, I was able to pull away—only slightly—to take the win for Segment 3.

No caption needed. (Photo credit: Joe)

Several miles of gravel roads lay ahead of us as we re-grouped and rolled on to the last aid station and then the start of Segment 4.

My sports psychologist, Dr. Kristin Keim, has been known to say “happy racers go faster.” My goodness, she is so right. We rolled through the central PA hills with ease, three abreast in the back country roads (don’t worry, Mom, there was virtually no traffic!). We discussed bikes, racing, the impact of Covid on our current lives and future cycling endeavors, politics, chamois and chamois cream, and we recounted old race stories. We were three unsuspecting friends riding together as if this was our typical weekend routine, enjoying each other’s company. For most of the ride, the only thing on my mind was “I feel so fortunate to have such great company today. I’m so happy I asked them to ride with me and they agreed!” oh and of course “damn, I have to pee AGAIN!?”. For these several miles, all the worries and the stress of racing that typically cloud my consciousness had melted away, leaving happiness and joy in its wake.

In every single photo taken of our group, I am smiling (even if it’s a slightly awkward smile). What a change from my usual race day seriousness. (Photo credit: Abe Landes/Firespire Photography)

After filling our bottles one last time, we rolled into Segment 4. Just as in Segment 3, Hayley and I settled into our own tire ruts. The nearly 100 grueling miles of riding that preceded this climb was making itself known in each fiber of my legs, as I called upon my body to give everything for one final push. Side-by-side, we were crushing the hill at a pace I didn’t think was possible this late into the course. Turns out, it wasn’t possible (at least not for me) and Hayley took off. Unlike Segment 1, I was able to keep her in sight the entire time. At one point, after Hayley had established her lead, she passed a very tall, fit-looking man who was also cruising his way up the climb. I eventually caught him myself and muttered the usual “on your left”. A couple minutes later, I heard an unexpected shifting noise and realized this huge guy was drafting off of me while we were going uphill! I didn’t have the spare energy to ask if my comparatively small body was actually making a difference for him, but I suspect the mental drafting helped in some way. Either way, I was flattered and still had enough energy to chuckle to myself while still keeping Hayley just a few seconds ahead. I never was able to catch her though. Damn, she’s a good climber.

I’m so darn glad Joe caught this one. (Photo credit: Joe)

After passing the “Segment Finish” sign, I re-grouped with Hayley, caught my breath, and noticed that both of us were smiling. I can’t claim to know why she was smiling, but I can tell you my own reasons. First, it hit me that the racing was complete but we still had nearly 20 miles of beautiful gravel and paved roads as well as some rail trail to enjoy before closing out the day. Next, I realized that I had pushed myself harder than I ever would have on my own, thanks to the competitive camaraderie fostered by my Roving Girl Gang members. Finally, I recognized that not a single one of the fears I had dreaded about riding as a group had come to pass. This was truly a day enriched by having the company of each other.

When we rolled toward the finish, I asked Hayley and Vicki if we could cross the line together. Of course, they agreed. After spending all day as a group, it felt like the perfect closure.

Rolling into the finish area to pick up our finisher’s whoopie pies felt somewhat anticlimactic because I honestly didn’t care who won the race. The day had already felt like a massive victory, after conquering my vulnerability and having such a wonderful time with Hayley and Vicki. I couldn’t have imagined a more perfect day on the bike.

In the end, my cumulative time for the 4 race segments was the fastest for Women and the 6th fastest overall. The Difference truly was the difference for me that day. And, as it turns out, I set an all-time personal best for my 20 minute, 10 minute, and 5 minute power -- a true testament to the day’s competition and a reassurance that all my 2020 training was not in vain.

Just as we had ridden the day as a group, so too we finished with a smiling podium photo (I promise we’re all smiling under our masks).

2020: the year of using your eyes to smile. (Photo credit: Dave Pryor)

So many things have changed since unPAved 2019, but some things will always stay the same. I might not have had a gut-wrenching race fueling experience you all hoped to read about, but I did still make some poor food choices that day. Specifically, I gave into my craving for a post-race milkshake and cup of fries at Red Robin. Yummm.

Keeping it classy by wearing a dress so I could eat Red Robin takeout food in the parking lot at 8:30pm on a Sunday night.

As we pulled into the driveway of our cozy cottage, the night air was crisp and the country hills were nearly pitch black. In the distance, I noticed a farmer navigating dusty fields illuminated by his tractor’s dim headlight. I knew it was going to take longer than usual to pull myself out of the car, so I remained in the passenger’s seat for a moment and breathed a deep sigh of relief as the day’s emotions washed over me. I smiled thinking about the remarkably amazing day spent with some equally remarkable women. My legs were exhausted and my heart was full.

This, I realized, is the feeling of being home.